What is effective in an accelerator?

For those of you not acquainted with the programme, Startup Chile is a governmental entrepreneurship-support programme based in Santiago, Chile, which is often identified as an “ecosystem accelerator”. In short, this definition means that its objectives are to foster entrepreneurship in Chile in both national and international actors, rather than financial returns on investments. Startup Chile supports entrepreneurs by providing participants with a 40.000$ cash grant and some services, including for instance office space. Participants are required to relocate to Santiago for 6 months. Since its inception in 2010 and until Generation 7 in 2014, i.e. the period taken into consideration in the study, the programme had received over 3000 applications worldwide and had funded over 600 startups. Starting in 2012, participants could compete in a pitch day after a few weeks in the programme, to access an entrepreneurial schooling programme with training and mentors. More recently, Startup Chile has expanded its offer to three programmes, from pre-acceleration to scale-up stage.

For those of you not acquainted with the programme, Startup Chile is a governmental entrepreneurship-support programme based in Santiago, Chile, which is often identified as an “ecosystem accelerator”. In short, this definition means that its objectives are to foster entrepreneurship in Chile in both national and international actors, rather than financial returns on investments. Startup Chile supports entrepreneurs by providing participants with a 40.000$ cash grant and some services, including for instance office space. Participants are required to relocate to Santiago for 6 months. Since its inception in 2010 and until Generation 7 in 2014, i.e. the period taken into consideration in the study, the programme had received over 3000 applications worldwide and had funded over 600 startups. Starting in 2012, participants could compete in a pitch day after a few weeks in the programme, to access an entrepreneurial schooling programme with training and mentors. More recently, Startup Chile has expanded its offer to three programmes, from pre-acceleration to scale-up stage.

The paper is “The Effects of Business Accelerators on Venture Performance: Evidence from Start-Up Chile” by Juanita Gonzalez-Uribe and Michael Leatherbee. The paper contains details on the tools and statistical methods used, including a web-based and social-media-based search, and a couple of surveys, together with all the numbers that one needs to establish a scientific base for their conclusions. Although I used to be good in statistics during my PhD, I confess I got a bit lost in the technicalities also because I did not have much time to go through the numbers, so I will skip the scientific details. Just, let me say as a caveat that in one survey the responses of schooled participants were only 13. However, the second survey received more responses from schooled participants, and the authors explain how they merge these results, and those of the online social-media research. As an additional caveat, raised by the author themselves, surveys might be biased because companies who are still going and are successful tend to respond more easily than those who have closed.

This said, what follows is a summary of the most interesting conclusions they collected from the data. I will freely edit some of the original text and mix with my own notes and understanding, so if you want 100% scientific guarantee of the following content please refer to the original paper. Also, I will add comments where I feel I have something to add, and would appreciate yours as well.

Here are the authors’ conclusions:

1. The entrepreneurship school has a significant impact on startup growth

By comparing the performance, according to a number of parameters, of startups who were selected for the entrepreneurship school and those who were not, the authors found that schooling has the following beneficial effects:

– Fundraising capabilities: from +21% (web-search) to +45% (surveys)

– Capital raised: 3x-6x

– Increase in valuation: 5x

– Market traction (venture scale): +23.8%

– Increase in employees: 2x

By “entrepreneurship school”, the authors refer to a set of activities in Startup Chile which provide entrepreneurship know-how, confer certification, provide access to distinguished international guests and encourages peer networking, increase exposure to the community, and involve greater supervision. These are the activities common to all professional business accelerators.

It is good news to hear that all the work made by accelerator core teams and mentors around the world (and I know what I am talking about) has a statistically relevant impact!

However, my experience suggests that the second selection step (i.e. the Pitch Day in Startup Chile) after a few weeks into the programme could have a strong influence: the core team has done a prolonged and more personal due diligence of the business ideas and the founders, so cherry-picking is facilitated and the quality of selection is much higher. I cannot gauge how much this selection can outmatch or not the power of entrepreneurial schooling, and, if I understood well, neither can the researchers.

Although I also have a deep feeling that the impact of entrepreneurial schooling is far from being negligible, I believe that it depends on the background of entrepreneurs: it is more impactful for first-time entrepreneurs or for people coming from long-term careers in other sectors, like scientific researchers, technologists, or industry managers. To these people, training in an accelerator can generate a dramatic change of mindset, from centred around their specialties to becoming customer-centred. Also, these people can acquire creative skills and design-thinking methodologies for problem solving, which are just not accessible in their career paths. In this sense, I agree with the researchers that accelerators are a new kind of MBA (see below).

2. There is no evidence instead that cash or coworking space have an impact on startup growth

The researchers could not find any statistical evidence that participants who received cash or coworking, but not the entrepreneurial schooling, would outperform non-participants (i.e. those applicants that were not selected in the first place).

There is a lot of debate in Europe on the advantages of being inside a coworking space, in terms of network, access to talent or advice, and community exchanges. Well, the researchers tend to exclude that these advantages have a statistically relevant influence on the development of startups. Moreover, neither does the initial cash injection of 40.000$ (more recently reduced to 30.000$).

I speculate that there are many factors which could explain this finding, among which:

– The actual situation in Startup Chile is unknown to me, but for sure a coworking space needs to be managed in order to bring value to their participants: the managers act as communication hubs, or keystones (cfr. “The Rainforest” by Hwang and Horowitt) and in some cases they can provide the “social network” advantage of accelerators (see below); if the coworking space in Startup Chile is not managed by keystones, this might partially explain its diminished effectiveness;

– As the authors themselves point out, in the case of foreign startups 40.000$ are mostly used to cover the cost of moving to Chile, so the money effectively useful for growing the business is much less;

– Frankly speaking, I believe that such a little cash injection is more of a bait to fly to Chile than a real help: that amount of cash can be easily borrowed from friends and family or obtained from business angels if the project has potential, thus it is understandable that non-participants who had a potential were able to raise that amount from other sources and could on average perform as well as the participants;

– Startup Chile, being the first programme of this kind that invested massively in worldwide marketing, attracted all sorts of people, from those who intended really to start a new venture to some smart ass digital nomads who managed to put together a project just to get a paid vacation (I personally know a few of this lot); this sourcing factor could partially explain why the performance of startups who did not pass the second step of the “Pitch Day” may not be as high on average.

Additional speculations by the authors

Besides these conclusions coming directly from the data, the authors also add some speculations of why schooling is so important. They derive them from interviews and opinions collected during their qualitative research.

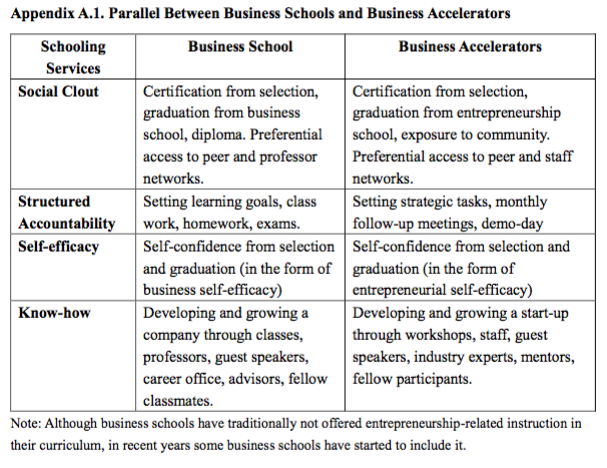

The authors believe that schooling provides four scarcely supplied entrepreneurial-capital-enhancing mechanisms:

(1) an increase in the “social network” of the founders — via access to business and fundraising connections of their peers, the programme staff, preferential access to foreign guest speakers, exposure to the broader community, and certification from being admitted into the school;

(2) the introduction of “structured accountability”: a commitment to publicly articulate and be held accountable for monthly development goals and tasks, checked out regularly by the programme staff;

(3) an increase in entrepreneurial self-efficacy or self-confidence as the recognition of being accepted into the school may help to boost entrepreneurs’ belief that they are capable of achieving tougher goals (the authors quote literature that has proven self-confidence to be correlated with entrepreneurial success); and

(4) the acquisition of know-how about building a start-up, as a consequence of workshops and the interaction with accelerator stakeholders and peers.

Points (1) and (4) are not surprising, and point (2) is particularly true for inexperienced startup founders who often lack project management skills. As to point (3), I would be impressed if that was true for most ecosystem accelerators. As for MBAs, admission to the ivy league or top universities worldwide can indeed boost one’s ego, but I do not believe that it is generally the case for any MBA. In this sense, ecosystem accelerators tend to be the easiest to access, because they do not select for financial viability and returns, but according to ecosystem metrics (e.g. jobs created, long-term retention in the region, network potential, and similar). These metrics bring to the admission of viable businesses, who however do not always exhibit high growth or scalable business models. Maybe Startup Chile is an exception, I do not know it well enough.

Personally, I believe that point (1) accounts for 60% or more of the explanation, with point (4) closely following in the instance of first-time entrepreneurs. The authors quote previous research, in which 32% of respondents of a programme-value-assessment survey (December 2012) mentioned that gaining access to a group of like-minded entrepreneurs was the most valuable aspect of the Start-Up Chile experience.

Entrepreneurship is a “technology that diffuses slowly”

The authors say that “founders may be unaware or underestimate the importance of entrepreneurial capital a priori. As suggested by Bloom et al. (2013), management is a technology that diffuses slowly. Moreover, effective management is the type of knowledge that may be taught and “learned-by-doing”. Likewise, we may expect knowledge about entrepreneurship best practices to also take time to diffuse. The program circumvents these informational frictions by providing examples, opportunities to gain experience, and by serving as a collective knowledge pool of best practices.”

So, they suggest, entrepreneurship -similarly to management- is a “technology” that diffuses slowly (I believe they mean “practice”). And they argument a parallel which is not new: where MBAs provide participants with “managerial capital”, accelerators provide startups with “entrepreneurial capital”. The difference stands in the skills and tasks required: whereas managers execute known business models in mature environments, entrepreneurs discover new business models in uncertain and immature environments.

I found interesting the analytical table that describes that parallel (note: they use “social clout” where I used “social network” above):